Kogin Stitching: practical aspects and bibliography

November 21, 2012

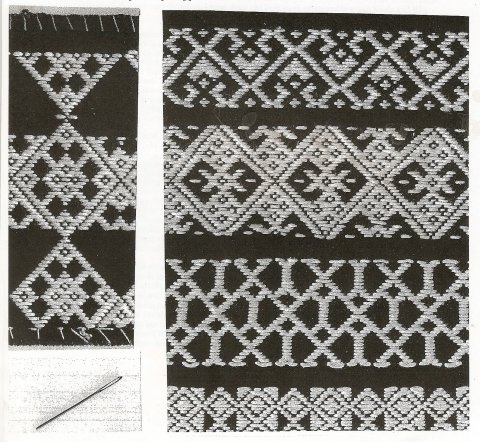

Scans of my own kogin work, unbleached cotton on commercial kogin fabric.

Left: Detail from a 4″ square. Authentic design of a diamond made up of six hana or flower motifs.You can see here that I worked the middle section in the proper manner (from one side to the other) but got lazy and ‘cheated’ by doing each larger diamond separately. You can see that I will have to undo the entire diamond at the bottomn – it is ‘out’ by a line where it meets the middle diamond.

Left lower: my kogin needle.

Right: Detail from a 13″-wide sampler using contemporary patterns of Takagi, formed into bands. Only the second from the top retains a classic, authentic look, such larger diamonds made up of two smaller diamonds of four ‘flower’ patterns each, joined by another, with the large blank spaces incorporating a single dash reminiscent of the ‘cat’s eye’ design. The third row is based on traditional diamond outlines joined in the middle by a classic ‘pillar’. The bottom row features the small ‘closed’ diamond or ‘soybean’ design element. The prominent areas of plain background in the first, third and fourth bands mark them as clearly contemporary patterns.

I’ve written posts on kogin stitching previously, but I thought I’d draw a line under my past experiences with this Japanese folk embroidery by being less objective and more subjective by describing my personal experience with it. I’ve also appended a bibliography. Compiled four years ago, I hope to do some more online research and try and update it sometime.

My approach was to work as “authentically” as possible, i.e. to get the feel of what it must have been like by stitching in unbleached cotton thread on commercial “kogin” fabric. By rights, I ought to have woven my own fabric then indigo-dyed it (lots of dippings into the dye pot to get it near black). In addition, I’ve compromised by opting for contemporary kogin patterns.

My limited experience of creating kogin can thus be summarised as follows:

* Modern commercially-available kogin fabric is usually dark blue. When blue-black and densely woven, counting the warps can be difficult and holding the fabric to a light source is the only way I can work, especially indoors. Considering this embroidery would have been stitched at night and in the dead of winter, perhaps the fabric was held up against some sort of candelight. Frankly, I went almost went blind trying to see what I was doing. Working more than one stitch at a time per needle stroke results in neater work, but runs the risk of gathering the fabric, resulting in pulling-in of the fabric at the sides. Mis-counting the wars is very easy to do, no matter how strong the concentration. Undoing one’s work affects the quality and look of the cotton thread.

* A thick, multi-stranded unbleached cotton yarns create the necessary dense stitching appearance of original kogin. Some dense stitching done in Japan of old takes on the appearance of a snow drift, of undifferentiated white, with the most marvellous of textures. A blunt needle poses fewer problems than a sharp one.

* Originally the stitching was done in sequential rows, from right to left. Work from right to left on one row and at the end of that row, turn the work upside down and work the next from right to left also. Diamonds were never created as separate large diamonds. It is truly very tempting just to create each diamond separately, especially since the back of the finished embroidery will be covered by a lining. However, original kogin, like blackwork in the West, really requires the back of the work to be as finely finished as the front.

* When working with traditional 13-inc wide fabric, it’s possible to cut lengths of thread for single rows, with small slip knots at each end.

* Reading modern-day pattern drafts can be disconcerting at first if one is used to cross-stitch patterns. In kogin patterns, each square represents not the space between the warps but a separate warp. When the square is blank, the thread passes to the back of the fabric. It helps enormously to keep in mind when stitching from a pattern to be fully aware of the fact that work can only be done over 1,3 or 5 warps.

* Simple embroidered bands, quite different from the diamond-shaped pattterns, were often used to mark off broader bands of work. Simple goemetric stitches, not unlike sashiko, were used in these bands. Patterns for bands appear in modern how-to books.

* Generally, original or ‘authentic’ kogin calls for hardly any underlying blue fabric to show through. This is not inconsistent with the original need to strengthen the fabric. Modern interpretations of the patterns (such as the ones I’ve stitched) call for much more of the ‘blue’ to show through. While still beautiful, the more ‘blue’ that shows through, the less close it is to ‘authentic’. White-on-blue seems to be accepted as classic kogin, though blue-on-white or red-on-white, even variegated thread, are contemporary alternatives. A large single diamond surrounded by plain blue is common these days, but is far from the original. Sometimes a large single diamond is surrounded by a “background” of stitches, again far from the original. In contemporary work also, single large diamonds are sometimes broken up into overlapping diamonds.

I wrote these notes in 2008 and haven’t gone back to kogin since. If I was to return, I’d probably attempt something less taxing on the eyes, e.g. red-on-white or blue-on-white. On my bucket list is the next ‘stepping stone’ from kogin, multicoloured nambuhishizashi. But for nambushishizashi, I’d have to weave my own fabric because all commercial support fabrics I’ve seen rely on squares, while nambushizashi relies on rectangles instead. I’ve tried stitching nambuhishizashi on commercial ‘square’ fabric and I ended up with ‘square’ diamonds instead of elongated ones.

That said, I have come across a kogin project by Phyllis Maurer (USA) in the magazine Inspirations (issue 62, 2009). Her chair pad (45x50cm, on navy 18-count Aida cloth using #5 pearl cotton in white and navy) is interesting because (a) it’s obviously much easier to stitch since one stitches both white and navy threads on white cloth, rather than white thread on navy cloth, and (b) its “flat” diamonds come close to representing the diamonds of nambushizashi.

Kogin – working from pattern books (2)

July 5, 2009

Hiroko Takagi. 95 pages. Published 2000. ISBN-4837706991.

This starts off with some excellent descriptions of the practicalities – how to set up your fabric, stop the edges from fraying, etc., as well as some nice single diamonds to stitch in small 12x12cm square format. It then launches into some contemporary patterns for contemporary applications such as napery, wall hangings, etc. The focus tends to be on friezes and linear designs, rather than strongly authentically original all-over designs, but it is possible to expand these linear designs to become ‘all-overs’.

The last six pages of life-size black-and-white photos of frieze designs, with patterns, endear themselves to a sampler and wall-hanging project. Some of the frieze and other patterns in the book are quite contemporary – given the amount of background showing through; some are more authentically ‘dense’ with little dark blue showing. For me, it’s a personal thing, but I like to know what the ‘original’ was before becoming familiar with modern interpretations of the original. Pages 2-32 are colour photos of cushions, table runners, bags, vests, screens; also copies in colour of traditional Japanese blockprints.

Highly recommended for its practical approach and for its excellent frieze/sampler opportunities. Having got the hang of friezes, one can more confidently tackle all-over surface patterns.

Kogin – Historical Overview

July 5, 2009

Etymology

Kogin is a form of whitework or counted running stitch embroidery specific to north Honshu. Closely related to teh other great country textile technique sashiko, kogin is known as sashi kogin, koginzashi and Tsugaru kogin and comes from “koginu” and “kogino”, a short field jacket which has been indigo-dyed and decorated with hemp thread stitching, created in Honshu and Kyushu Islands. Kogin can refer both to the stitching and to the finished fabric. Over time and with the introduction fo white cotton from urban areas, as well as from the promotion of local handspun cotton, kogin has come to represent blue-and-white embroidery from rural Japan. It is specific to the region associated with the daimyo family of Tsugaru, an area also known formerly as Tohoku which today is known as Aomori Prefecture. The dense tight stitching reinforces the bast asa (hemp or ramie) fabric and is said to mimic the heavy snows typical of Tohoku winters. The worst of the winters resulted in rice crop failures roughly every six years, so that Tohoku came to represent all that was very distant and rural, poor and backward, compared to urban Kyoto and Edo.

History

Kogin was first documented in 1685 as elaborately stitched fabric, but it seems to have crystallised as a textile technique thanks to sumptuary laws forbidding the wearing of cotton. The Frugality Act for Farmers, enacted in 1724, prohibited peasants from buying or using cotton or silk cloth and the Tsugaru rulers took these sumptuary laws seriously. As a result farmers around Hirosaki City, the stronghold of the Tsugaru overlord, were thus forced to limit their wardrobe to bast fibre garments. Asa fabric was strong but cold, so asa thread and later cotton was used to improve the fabric, a surface addition which conveniently skirted around the sumptuary laws. Indigo-dyed blue thread on white asa fabric was mentioned in a travel memoir of a samurai in 1788 and another memoir in the same year mentioned white thread on blue fabric. Perhaps it was from this time onwards that the look of kogin as being white-on-blue became the ‘classic’ we know it today.

Embroidery cotton and modern kogin

In the 1830s, cototn thread came to be manufactured in Tsugaru itself and cotton was permitted to be worn by ordinary Japanese in early Meiji Period (1868-1712) so Tsugaru farmers developed the ‘Sunday best’ version of kogin accompanying cotton kimono, as opposed to the hard-wearing everyday field garments. It is thought that the embroidery was used on formal wear initially and as the kogin became worn, it was later incorporated into work clothes. Once the railroad came to the area in 1892 and later via the Tokyo-Hirosaki railway line in 1894-5, kogin declined rapidly in contrast to mass-produced clothing from the city. Within the larger mingei craft movement of the 20th century led by Soetsu Yanagi (1889-1961), kogin was revived by the collector/designer Teizo Sohma (Hirosaki City, Tsugaru) and practitioner Setsu Maeda (born at Tsugaru near the end of World War I) who was named a National Living Treasure in 1962. Naomichi Yokijima, of Hirosaki City, spent the period between the 1930s and 1960s documenting kogin, giving rise to his book of 1966. He founded the Hirosaki Kogin Research Institute providing a commercial outlet for local embroiderers.

Kogin is still worn in the dance performances of Sanaburi-Arauma-odori in Kanagi City, north Tsugaru; mishima kogin features int eh costume of the horse-keeper in the performance. After World War II, kogin was incorporated into art classes at schools in the local area. Publication of books has assisted in its being maintained in Japan, as well as abroad, as interior decor. Examples of classic kogin appear to be few and far between, rarely coming on to the textile market. I personally saw only one example in Kyoto, admittedly far from its native land, in the Orinasu Weaving Centre display of Japanese textile techniques. One kimono with kogin has been on sale on eBay for a very long time with an asking price of $US3,800. As a craft commodity of north Honshu, it obviously features heavily in the promotion of Aomori Prefecture and is undoubtedly a feature of tourist souvenirs there.

Garments

Classic kogin involves a plain dark blue kimono with an embroidered yoke over the shoulders to the waist. Below the waist and the arms, the fabric remains plain or with extremely restrained sashiko. The long sleeves on extant examples show this to be the Sunday-best variety since short sleeves would have been worn in the fields. The embroidered bodice was treated with great care and kept for a long time, while the rest of the kimono got wet in the rice fields. The yoke is invariably older than the rest of the kimono garment. To hide stains and age, it can be indigo overdyed or over-embroidered in the opposite direction to the weft direction of the original embroidery to prolong its life.Museum examples as illustrated in Ogikubo’s book show the yoke by itself, sometimes still attached to the lower kimono without sleeves, sometimes with the sleeves attached, sometimes as a short jacket and at other imtes a long-sleeved formal kimono. Some examples show different patterns in the one piece in subtle patchwork technique, obviously salvaged from various different pieces. The Okigubo book shows a single example of indigo over-dyeing.

Technique

Kogin stitching uses a straight, horizontal running stitch, sewn from one side to the other, commencing from the centre out to either side at the centre point. The base fabrics were generally loose to allow easy counting of the stitches. The diamond patterns are created by the use of plain weave fabric: even weave creates ‘square’ 90-degree diamonds and uneven weave creates elongated diamonds, i.e. more warps than weft per inch. In some examples of kogin and Nambu diamonds, it’s possible to discern both types of diamond in the one textile, which can be disconcerting to any modern-day embroiderer trying to replicate a pattern. Small diamond patterns become the elements of much larger overall diamond patterns. Commentators mention neko no ashi (cat’s foot) and sayagata (the linked swastika), especially in relation to east Tsugaru; abacus stitch (soroban sashi) is used in the west. Western commentators talk about “flower”, “soybean”, “pillar”, “cat’s eye” and so on, as being the base design elements.

Sashiko and Nambuhishizashi context

There are several characteristics of kogin which set it apart from kogin (literally, “little stabs” or “little stitches”) and the kogin-like diamonds embroidered in the nearby Nambu area to the east. Some kimono stitched with sashiko often have heavily-stitched areas around the shoulders, so it’s not too much of a stretch to see how embroiderers would have developed as a consequence a very dense ‘sashiko’ in these parts of the garment, which may have eventually developed into kogin. In kogin, cotton is used; wool is used in Nambuhishizashi (literally “sashiko-type diamonds from Nambu”) mainly because it is a much later style, from the late 19th century when coloured wool from urban areas became available by rail. Nambu faces the Pacific Ocean which was outside the shipping lanes of the inland Japan Sea. Sashiko designs utilise stitches which can go in any direction; in kogin, stitches go only in the direction of the weft. In kogin, designs are created by crossing wefts over and under odd numbers of warps. Small diamond shapes are thus created just by crossing 1,3 and 5 warps. Crossing 5 warps is invariably the longest float stitch used in traditional kogin – longer stitches are found in contemporary work. Crossing 4 and 6 warps doesn’t happen; 7 is made up of 3,3 and 1, 8 is made up of 3 and 5, etc.

Regional variations

It’s thought that each village and area developed its own patterns which spread through intermarriage as a wife would go and live with her husband’s family. There are several regional variations associated with kogin, linked to the areas east and west of and at the mouth of the Iwaki River. the west (Hirosaki City), nishikogin, is made up of patterns with dense stripes over the shoulders. The north (Kanagi City), mishimakogin, has three wide horizontal stripes, like bands in a sampler, three on the back and three on the front. In the east (southern Aomori or Tsugaru, its former name), higashikogin has a large overall pattern, done in thicker thread, uninterrupted from front to back. Originally, girls would start embroidery at age 7 and would learn kogin at around 10. By their marriageable age of 16, they would have made three coats for their future husbands and three for themselves as part of their trousseau.

Kogin – working from pattern books (1)

July 5, 2009

Kogin needlework is not widely practised in the West and source material is not easy to come by, whether those patterns be authentic Japanese designs or contemporary Japanese designs or contemporary Western designs.

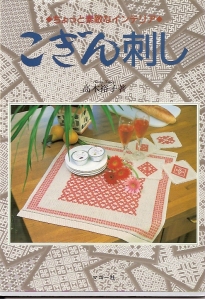

This book is entirely in Japanese, including all the colophon details. It has the feel of the 1970s or 1980s about it, a period when books on traditional Japanese craft began to be published for a mass market keen on the nostalgia of previous generations and disseminating ‘studio secrets’ no longer directly linked to the traditional method of either apprenticeship or studio ‘learning’.

After four pages of history and background, including a map of north Honshu, there are some thirty-five odd pages of patterns and black-and-white photos of the finished pattern, at around two or three per page. They are strongly authentic, traditional-looking all-over patterns. A further ten pages follow with more patterns but with modern applications in mind, such as purses and zippered containers. Only in the very last two or three pages do we have the large single diamonds set against a plain background, which is really the sign of modern late-20th century kogin, both in Japan and in the West.

On pages 34 and 35 there are three patterns which are derived from the ‘flattened diamond’ of Nambuhishizashi. In the lack of any proper more comprehensive Nambu Diamond patterns, these are a good start to the style.

Highly recommended, given that it sticks really quite close to the authentic Japanese kogin aesthetic.

Kogin – Starting out…

June 29, 2009

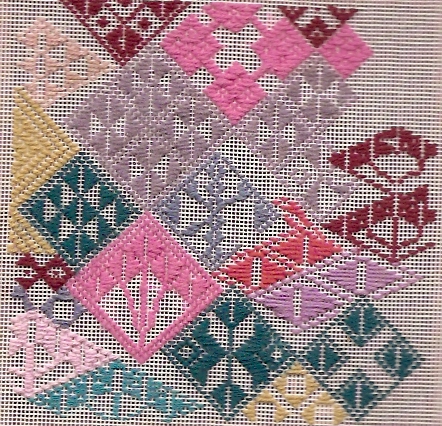

My initial experiment with kogin was playing with a wide range of yarn types – cottons and wools – and different surface designs on a piece of tapestry canvas on a stretcher. The classic monograph on Japanese textiles to my mind is the William Rathbun, Beyond the Tanabata Bridge, and in it there are some particularly good close-up photographs of kogin and Nambuhishizashi. I supplemented this material with the excellent photobook of kogin and sashiko, published as part of the Kyoto Shoin Art Library of Japanese Textiles series. I am as much drawn to the coloured wool used in sashiko diamond work from Nambu, as to the austere blue-and-white classic kogin work of Eastern Tohoku.

From there, it was a matter of buckling down and working with proper unbleached kogin thread on a very dark blue commercial kogin cloth, as distributed in Australia by Sanshi. This particular cloth was almost black; I’d recommend a paler colour where available if you don’t want to work in bright direct light (and a good white cloth underneath your work). I was forever holding my work up to the light to see that I’d stitched the correct row of holes – developing in the process a formidable admiration for the women of Tohoku working in winter and at night by candelight.

Only the second from the top is what might be referred to as authentic-traditional; the others are modern takes on traditional motifs. I’ll dig out my notes from these early days and share them with you.