Shibori in Kyoto

August 7, 2009

successors to this labor-intensive tradition have dwindled. In the past, these production centres depended on the handing down of

traditional techniques, reviving lost methods, and restoration work. In order for this tradition to continue and develop, great efforts

are needed.”

Ando also structures his book with chapters devoted to shibori from Tohoku, Nagoya, Kyoto, Kyushu and Okinawa and his examples include dyeing with gromwell and madder as well as indigo. I think it’s very important for me to reiterate the cotton/silk dichotomy in terms of Arimatsu/Nagoya and Kyoto, especially if you’re familiar with the recently-released Wada DVD on Arimatsu shibori: cotton at Arimatsu, silk in Kyoto.

FUREAI-KAN – permanent exhibition

I’ve mentioned previously how this museum is just about my favourite in Kyoto – I guess because it’s modern and new, and has a lot of detailed information in English on traditional textiles, and because the staff are very helpful and it’s not over-run by tourists. It is an ideal place of sit and meditate (in an otherwise hectic city!), especially by the waterfall which is part of the building’s architecture.

The Fureai-kan Museum has large areas devoted to yuzen and shibori, and smaller areas devoted to loom weaving, braids and other textile arts specific to Kyoto. The loop video associated with the shibori display describes the following kyo-kanoko-shibori(1) (“fawn-dot shibori from Kyoto”) processes:

– Shitaechookoku(2) (punching lines of holes in the paper stencils with a metal punch)

– shitaesurikomi (with holes punched in the paper stencil, the stencil is then laid over the silk and dye is applied with big round

short-bristled brushes)

– hitta-shibori (tying the tiny kanoko knots, finishing each with a sharp `clicking’ to secure them with a final knot)

– oke-shibori (tapping nails into the fabric to secure it as part of the dyebath process and assembling the wooden dye “reels” whereby

the undyed part of the fabric is secured in between the wooden halves of the massive reel structure which is immersed in the

dyebath; this use of large wooden structures to leave large sections of the background undyed, or dyed another colour, becomes obvious

when one sees the finished kimono; the wood absorbs the surrounding water while the linen ropes repel it, causing the linen to tighten

around the wood)

– boushi-shibori (linework with tight single threads)

FUREAI-KAN – temporary exhibition

The foyer of the Fureai-kan has three very large glazed exhibition areas. In October 2003, they exhibited Kyoto dolls; to October 11,

2007 they exhibited kyo-kanoko-shibori. There were several complete kimono on show. These kimono were surrounded by several dozen large framed samples, set in mattboards like paintings or prints: a very large finished piece of shibori set above a smaller pre-dyed piece showing the knotting in place. No photography allowed.

NISHIJIN TEXTILE CENTRE

At Nishijin Textile Centre, a demonstrating craftsman sat cross-legged on tatami punching holes in white paper (the shitaechookoku

mentioned above). My photos, taken while the craftsmen was away at lunch, show the paper kata, the mallet and punch and

the knotted fabric ready for dyeing. Regarding stiff white paper vs persimmon tannin-dyed brown paper as used for the cartoons, note that Ando has a photo of both being prepared for the knotter.

I’ve mentioned previously the hourly kimono parade, featuring half a dozen models. At least one featured a predominantly shibori-

patterned kimono (white dots on a dark purple ground) and at least one obi with shibori dots. As previously indicated, shibori is tastefully combined in these instances with other techniques such as yuzen and embroidery. It’s worth adding that shibori is used extensively as the technique to decorate the obiage, what I call the obi `under-clothes’ used to fill out the obi to make it look even and flat. I imagine the raised surface of the shibori helps in this regard. As you’re probably aware, obiage are sold with obijime as complete `obi’ packages. I can’t help also noticing the similarity, at least in academic sense, between the female shibori obiage sash and the informal men’s obi sash which also calls for some shibori.

Here a plain gold obiage behind an obi decorated with shibori dots on a black background.

See the shibori-patterned obiage peeking out at the top of the obi on these shop mannequins.

KYOTO SHIBORI KOGEIKAN

Kyoto Shibori Kogeikan is one of the tourist establishments described previously, though smaller than its yuzen and shisu

counterparts (though size-wise on a par with Adachi Braiding Centre). There is a small shop area showing a range of finished

articles. Upstairs visitors are shown a short DVD of shibori and nearby a range of techniques is on display.

A small room is set aside for those wanting to have a go at knotting a small handkerchief: this involves kneeling in front of the wooden stand and, with the fabric already threaded-up in line with the surface design in advance and the knotted ends ready to fit in the dai, working two types of knots: the kasa-maki `umbrella’ and the nui-shima `single-line’. Bascially all I had to do was learn to wrap the pre-prepared thread around and around in the maki for the large flowers, and pull the pre-stitched threads tight and tie them off for the nui-shima. The handkerchief is then whisked away for a hotwater bath (wet fabric allows the dye to penetrate better than dry cloth) followed by an 8minute dyebath, drying using a hairdryer and final (dramatic) removal of the knots. In true Japanese style, it is folded and boxed; the texture is never ironed out flat – this shows that the item was hand-made.

The original patterned white silk is obvious despite the over-dyeing.

Much is made of the fact that most of the work these days is done by machine and that some is a combination of machine worked kanoko dots and hand-made `special effect’ single focus knots. Obviously hand-knotting the shibori is diminishing these days because a shiborist

might take a day to knot three lines of dots and a kimono may have up to many thousands of lines of dots. Plainly my humble tourist

effort at a few shibori knots made much more sense when I went back to see the Fureai-kan exhibit a second time.

EXAMPLES

I’ve scanned a red piece (7″ x 12″) bought from a Nishijin retail outlet, adjacent to Nishijin Textile Centre in Horikawa Street,

which specialised in small pieces packaged in plastic, I suspect aimed at the ningyo/doll market. The smaller knots were probably machine-made but I like to believe some of the larger focus knots were hand-made.

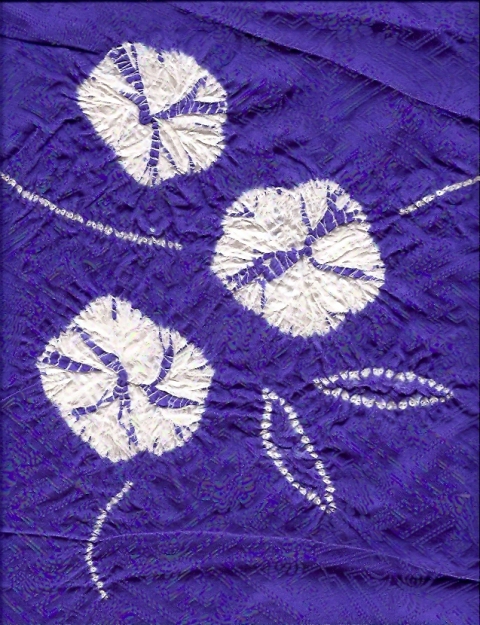

Smaller fragments, 13x16cm, were hand-dyed and set into window cards, sold by Konjaku Nishimura, a small traditional shop selling

textiles, surrounded by antique shops, in Nawate St, Gion Quarter, Kyoto (www.konjaku.com). This is a highly-recommended shop for anyone interested in traditional textiles visiting Kyoto; what’s special about it is it’s enormous range of textiles. As noted previously, I kept coming across kimono in Kyoto which featured shibori in combination with other techniques such as yuzen and embroidery.

I visited Mimuro kimono shop in Kyoto, an extensive business over several floors, but I was accompanied by a sales assistant

throughout and didn’t have the presence of mind to ask for men’s obi in particular; I spent a lot of time fending off offers to buy –

entering a shop in Kyoto has strong implications of intent to buy, while window-shopping outside is just that. Mimuro had an astounding

range of products and I ought to mention being shown two or three examples of braided obi known as sanjikku karaori obi

(literally `three-system’ kara-ori). I still haven’t managed to work out what I was looking at but it was an informal, summer obi, very

light in weight and light in colour. It appeared to be made up of lightly braided round karakumi diamonds, with a matching obijime

which looked distinctly Peruvian in character. In the simpler examples, it looked like three long andagumi/plain weave braids

linked at the edges, while another example seemed to involve different textures of yarn.

Footnotes

(1) Ando describes silk Kyoo-kanoko as a generic term for Hitta-kanoko shibori.

(2) Ando indicates that not even a rough sketch (and perhaps not even a kata/cartoon) was drawn to make Kyo-kanoko in Edo Period, all

the dots being bound “using the sharpened sense of the binder’s fingers”.

Bibliography

Ando, Hiroko Japanese tie-dyeing. Kyoto, Kyoto Shoin Art Library of Japanese Textiles vol.11, 1993. ISBN-4763670468.